This is the second out of two blog posts that concerns the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences in Pakistan. Read the first blog here.

Lockdown is the only effective precaution being used by most of the states in the COVID-19 crisis, and is something alien for the current generation. It has added economic hardships to those who depend on daily earnings and irregular payments. It has also added to the frustration of well-off people, as the virus has brought their social life to a halt. In addition to Personal Protection Equipment (PPEs) and precautionary measures such as hand washing and physical distancing, demand for psychological support is also on a rise, as many people confined inside their homes are unable to handle their anxieties and stress.

In the West and other developing countries, there are efficient systems responding to the challenge of a health crisis and limiting its impact on rights of their citizens. However, the situation in developing countries – particularly in South Asia – is quite different. The virus and its wide impact have exposed the fragility of the poor governance models of these countries.

Pakistan is no exception. The country is in deep crisis and each passing day there is an increase in the numbers of COVID-19-positive cases and related deaths amid an atmosphere of confusion and chaos. Fundamental rights – particularly human rights – are one of the causalities of the coronavirus crisis globally. However, the difference is that of data collection and reporting systems. For example, it was reported a 30 % increase in domestic violence in France within only one week of lockdown. There is no such data from Pakistan, as there is hardly any monitoring and reporting system in place.

Human rights in Pakistan

There should be a clear distinction between what is a health emergency and a general emergency. The chances of abuse of power by the authorities as well as private actors are much greater in countries that lack independent oversight and have a low literacy rate. In Pakistan, the COVID-19 emergency has taken precedence over everything else, as civil and military authorities are fully focused on the virus, and the media is hardly finding any time to report on anything else but the pandemic news. The country was confronted with several key human rights challenges at the pandemic struck. These included restrictions on right to expression, association and assembly, violence against women and children, persecution of civil and political activists and violence against religious minorities.

The Reporters Without Borders ranked Pakistan at the 145th position among 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index 2020, released earlier this year. Similarly, the country is ranked at 151st place in the Global Gender Gap Report 2020, depicting the dismal situation of gender rights in the country. Though a number of prisoners were released from prisons after the coronavirus outbreak and there has been a lenient behavior towards inmates, not a single person from the list of enforced disappearances has been released.

"In Pakistan, the COVID-19 emergency has taken precedence over everything else, as civil and military authorities are fully focused on the virus, and the media is hardly finding any time to report on anything else but the pandemic news."

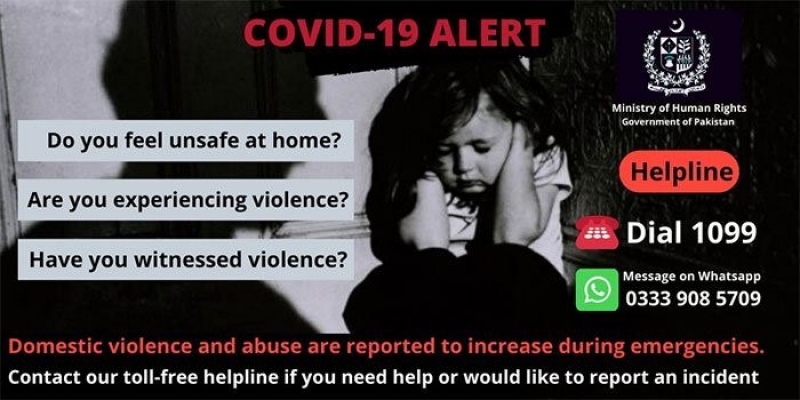

The ministry of Human Rights announced on March 30th that they were setting up a helpline, but human rights activists say it is too little and too late. First, the helpline is based in Islamabad, and secondly it is not in the reach of most people. Those who tried to call the helpline faced message recording machines, and they never got a call back. This is a common story of most of the helplines in Pakistan in ordinary situations, let alone in crisis situations.

Both the Department of Women Development and the Department of Human Rights in Sindh were running helplines, but the provincial commissions and ministries are closed due to the lockdown and so are their helplines, as these were not considered as “essential services.” In such a situation, it is difficult to find an exact picture of the human rights situation during the coronavirus lockdown and the mass confusion. However, human rights and women rights activists believe that there would definitely be an increase in domestic violence, as people are confined in their homes, which causes a lot of stress. “There are both psychological and economic pressures, resulting in family quarrels leading to domestic violence,” says Mehnaz Rehamn, Resident Director of Aurat (woman) Foundation in Karachi.

Though domestic violence is not restricted to certain demographics, the situation in slums, particularly in big cities like Karachi and Lahore, is the worst as poor families of 8-10 people often live in just a single room. This naturally leaves many in vulnerable situations and exposes them to domestic violence. Furthermore, children are, together with women, also one of the largest vulnerable groups in Pakistan. Child abuse is rampant in ordinary circumstances, and the situation might be worse in this crisis situation. The independent institutions like National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR) and National Commission on Status of Women (NCSW) remain dysfunctional for the last several months due to “red tapism” (bureaucratic hurdles).

It is not too late to make these institutions functional, along with making the existing helplines, shelter homes and other human rights related facilities functional, to ensure better protection of human rights during these testing times.

The NHRF invites different actors within the human rights field to contribute on this blog. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors.