My experiences have shown me that our challenges can be tackled when people come together.

I am 28-years old and I have progressive deafblindness. The word ‘progressive’ here has nothing to do with growth or positivity. It means that I am losing my ability to see and hear every single day, bit by bit. All I know is that I have to deal with it positively.

Growing up in India, I was confined within the four walls of my home. Safety meant never being out of my parents’ sight. I used to be scared to go out. Violence against women is widespread here and we often don’t feel safe. Many girls are limited to housework and marriage and denied our own identity.

This lack of safety and access robs women with deafblindness of our independence. My brother also has deafblindness, but he can do things I never could, like living away from home, travelling independently, and communicating freely with everybody.

India is a conservative country: people can’t sit with a woman for long or touch my hand to spell words in my palm. Distance must be observed. So I either had to stay at home, or have someone with me.

Many people also aren’t sensitive to our needs. Family members might say to me: “You are not able to see, who will marry you?”.

My experiences have shown me that our challenges can be tackled when people come together. Shrutilata

Getting an education

At school I often felt jealous of other students. I found it hard to socialize, my classmates wouldn’t sit with me, and teachers didn’t meet my needs. I couldn’t see the class board from my seat.

I was desperate for change to begin: to feel included, and to have a normal life like anyone else.

After I finished school I got depressed. This was when my disability really started to worry me. I was stuck at home, wondering ‘will I ever get a job?’, and I took my frustration out on my family.

Looking back, I would tell my younger self that when you have reached your absolute worst point, think that it will only get better from here. And learn about your disability, because it is the key for new opportunities.

For me, real change came when I took up a course in physiotherapy at

an NGO in Gujarat, 90km from home. I thought ‘why not?’ This was my

first time away from home, and learning to be independent.

When I graduated, they said I was the first person with deafblindness in India with a physiotherapy diploma. Then I got the opportunity to lead a network of 200 adults with deafblindness with Sense International India, and advocate for our rights.

The power of technology

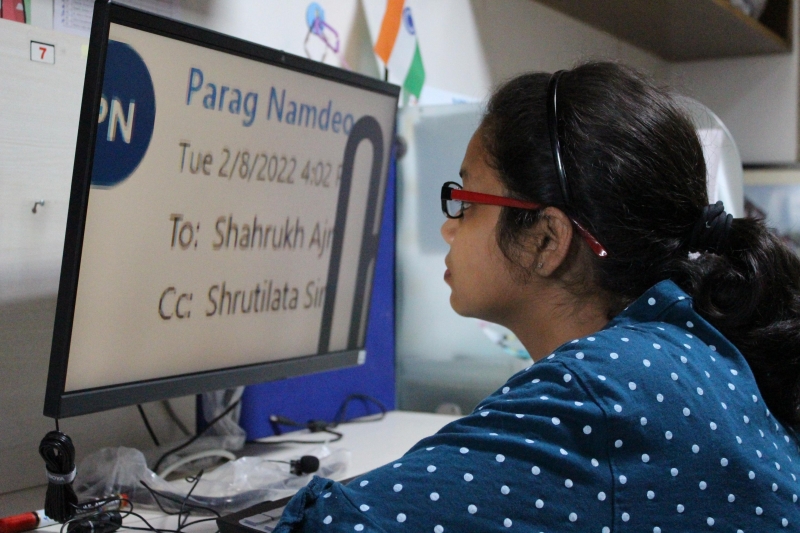

Tech companies need to realise that we are their consumers too. I’ve become independent by having access to technology and other people being sensitive to my needs.

Imagine us, two women, both with deafblindness, travelling across the world, exploring a new country and a UN event on our own!

I recently travelled to the United Nations World Data Forum in Switzerland to support a girl who had won a video contest.

Technology is the key. And accessibility is not a check box: it must be mainstreamed. When tech companies introduce new products, they need to consider us, no matter what. Having a phone that magnifies text now means I can order a cab, pay for things in shops, send voice messages, use Google transcribe, and go out into the world and flourish.

Many girls and women with deafblindness can’t enjoy their basic human rights. So I want to send a powerful message that we all need a chance to be both independent, and safe.

Technology is the key. And accessibility is not a check box: it must be mainstreamed. Shrutilata