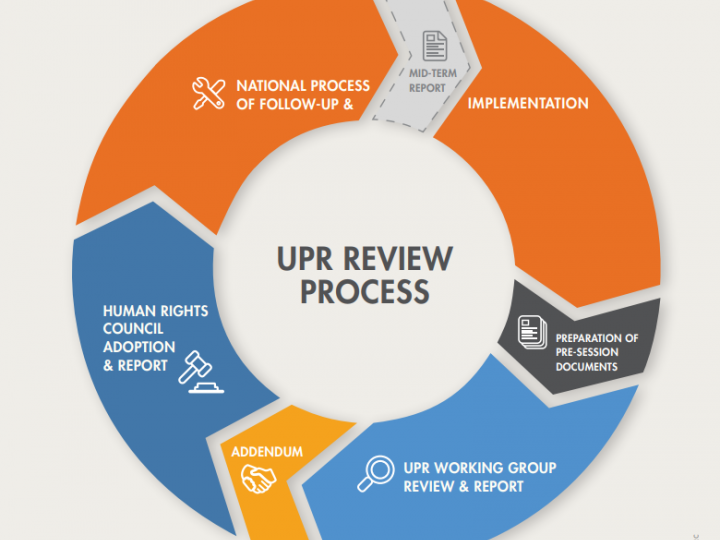

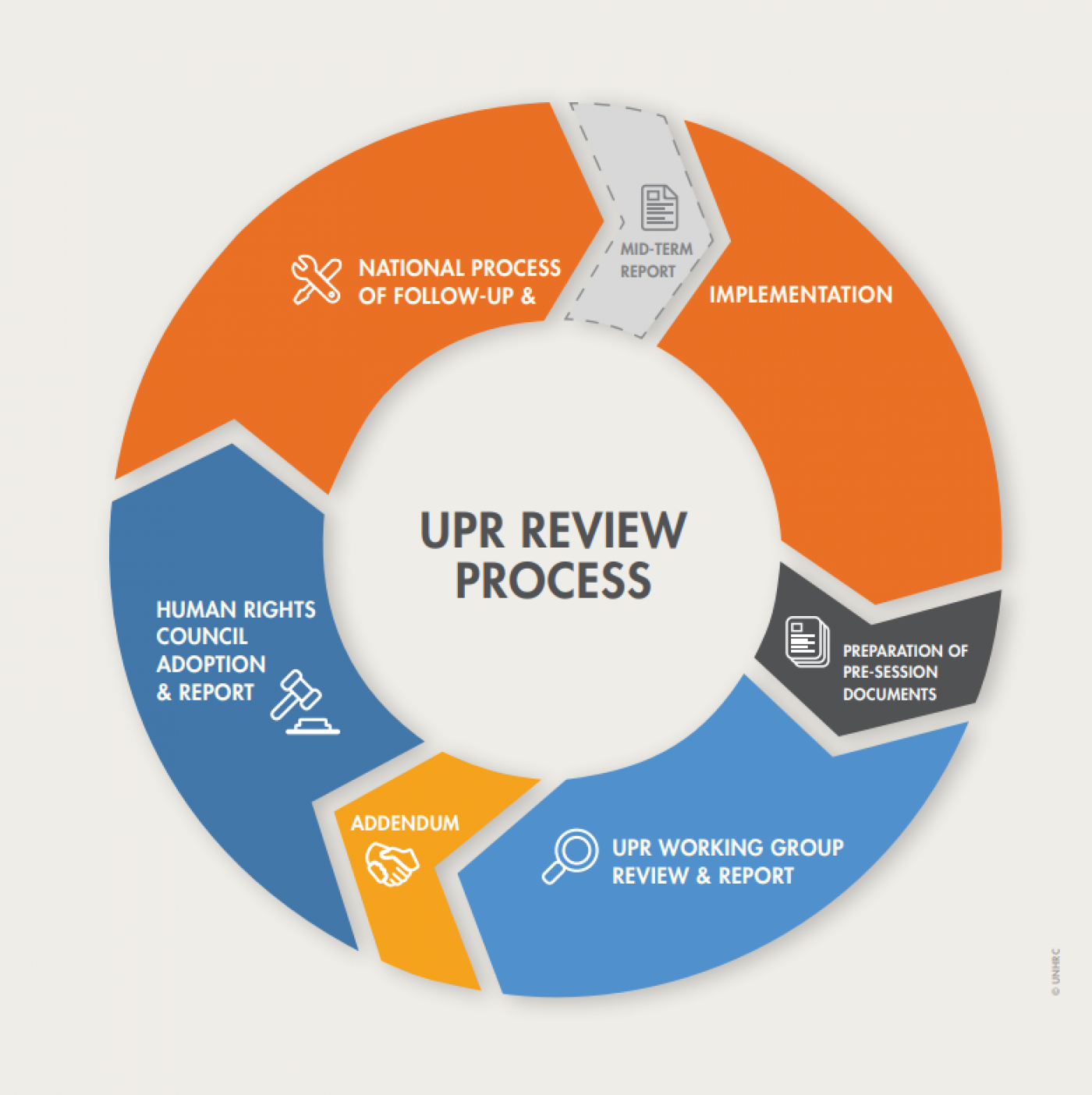

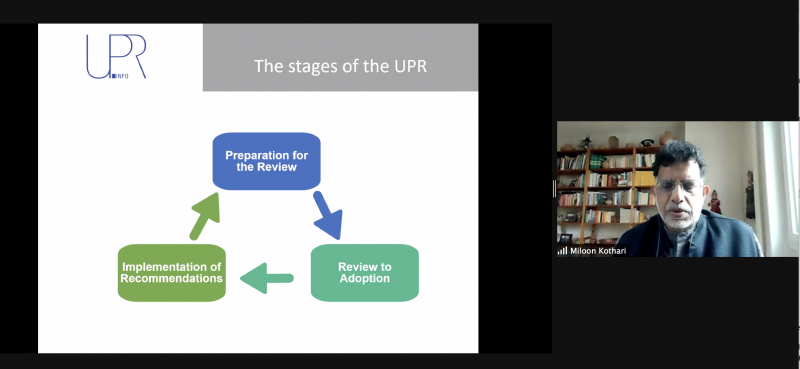

The workshop was facilitated by Miloon Kothari, who is the President of UPR Info, former UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, and member of the NHRF’s Advisory Board. The workshop started with an introduction of the various UN human rights mechanisms, with an overview of their structure and mandate. Next, the UPR system within the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) was explored in great detail.

Facilitator Miloon Kothari provided a detailed presentation of the role of civil society in the UPR process, which has led many governments to collaborate and work together with civil society actors. Civil society members can play an active part in the preparation stage, the national consultation stage, as well as in the review stage. NGOs have a particularly important role to play in conducting advocacy work to ensure that countries accept recommendations, by meeting with government representatives, the parliament or inter-ministerial committees. NGOs are also well placed to advocate for the implementation of the recommendations made, by for example issuing a press release or a public statement and conducting campaigns on social media. Miloon Kothari stressed the importance of linking the recommendations with concluding observations from various UN Treaty Bodies, Missions from UN Special Rapporteurs or Regional Human Rights Mechanisms. More active civil society organisations can play a significant role in contributing to the implementation of the recommendations, while more passive civil society organisations can play a great role in monitoring and conducting research.